This article appeared in The Reading Teacher, April 2004

BOOKS

TO LIVE BY:

USING

CHILDREN’S LITERATURE FOR CHARACTER EDUCATION

Good character consists of knowing the good, desiring

the good, and doing the good.

Thomas Lickona (1991)

The notion that schooling should be used to instill goodness in children is as old as schooling itself. Plato for instance, said, "Education in virtue is the only education which deserves the name." However, the practice of character education has changed focus, changed names and fallen in and out of favor in schools throughout our history. Sometimes the focus has been more on religious indoctrination as in the early Puritan schools, and sometimes more on values clarification as in the 1970's work of Kohlberg. Regardless, of what we call it, or how we focus it, character education is an enduring idea. This article will discuss what character education means now, explore why schools should be involved in it, and finally examine ways to integrate character education into the curriculum by using children's books.

Background

Information

Definition

The word

"character" comes from a Greek word that means "to

engrave." Literally, then,

character traits are those markings engraved upon us that lead us to behave in

specific ways. Ryan and Bohlin (1999)

defined character succinctly as "the sum of our intellectual and moral

habits." (p.9). Schools, of course,

are hoping to instill good character markings rather than bad in their

students, but whatever marks are engraved upon a pupil will lead to

intellectual and moral habits that in turn lead to behavior.

Society is in agreement about what constitutes a good character trait. In fact, numerous published lists of virtues are remarkably similar in content. C. S. Lewis (1947) drew from many diverse cultures and religions and identified the common virtues of kindness, honesty, justice, mercy and courage. The Character Counts Coalition listed trustworthiness, respect, responsibility, caring, justice and citizenship as core virtues (Josephson Institute, 2000). From the Greeks to the Boy Scouts the enduring core values we live by are very similar and widely accepted. Character education is the encouragement of these virtues in our students.

The Role of Schools in Character Education

Ryan and Bohlin (1999) listed five important reasons why schools should engage in character education. The first two reasons are historical. Great thinkers from long ago and from divergent cultures, have reminded us that the purpose of schooling is to not only help students become smart, but also to become good. The founders of our nation retained this belief. In fact, democracy was considered unworkable without an educated and morally responsible populace.

The next two reasons have to do with current legal and societal mandates for character education. Character education has been recently endorsed by federal law and by many state laws. Guidelines established in 1995 by the U.S. Department of Education reminded schools that while they must remain neutral on religion they were obligated to actively impart civic values and a unifying moral code (Vessels and Boyd, 1996). In addition to these legal mandates, society repeatedly confirms its desire for schools to teach character. In a recent Gallup poll (as cited in Ryan and Bohlin,1999), 97% of respondents favored the teaching of honesty, 91% favored teaching acceptance, patriotism, caring and courage, and 90% wanted the Golden Rule to be taught.

Finally there is the argument of inevitability for character education in schools. Wynne (1992) stated, "schools are and must be concerned about pupils' morality. Any institution with custody of children or adolescents for long periods of time, such as a school, inevitably affects the character of its charges." (p. 151). Many developmental theorists, such as Piaget, Kohlberg, and Vygotsky stressed that children continue to develop their moral codes during their school-age years, and character development, for good or ill, will take place during these years. These developmental theorists and Wynne (1992) would accept that the literature students read will instill character traits in them unconsciously even if these are never discussed or addressed directly in the classroom. However, schools would be wise to be intentional in shaping this development toward good by consciously using the existing curriculum for character education.

Integrating Character Education into the Curriculum

Repeatedly authors have affirmed the need to integrate character education throughout the school day if we hope to influence the behavior of students (Noddings, 2002; Ryan, 1996; Leming, 2000). One of the easiest ways to integrate character education into the curriculum is through the literature we ask children to study. Kilpatrick, Wolfe & Wolfe (1994) reasons for using literature study as a prime place for character education included the fact that stories provide good role models for behavior as well as provide children with rules to live by. Guroian (1998) agreed that stories are much more effective than mere instruction in character for awakening what he calls the moral imagination. Guroian especially valued the use of metaphors in stories for helping children connect experiences and morals. Both he and Bettelheim (1989) specifically advocated the use of fairy tales for character education.

Choosing Your Books

O'Sullivan (2002) claimed that a wide-variety of children's literature could be used for character education as long as teachers choose worthwhile books, move beyond literal to critical understanding of these books, and are intentional in focusing on the development of character during literature study. Criteria for choosing books should include:

·

Well-written books containing moral dilemmas,

such as Princess Furball by Charlotte Huck for primary children or Lyddie

by Katherine Paterson for older students.

·

Books with enough depth to allow moving beyond

literal comprehension, such as the picture book, Knots on a Counting Rope

by Bill Martin Jr. or the chapter book, The Giver, by Lois Lowry.

·

Books with admirable but believable characters

about the same age as students, such as Thundercake by Patricia Polacco for younger students, and The Moorchild by

Eloise McGraw for older ones.

·

Books across a wide range of cultures and with

both boys and girls as lead characters, such as the picture book, Rough-Face

Girl by Rafe Martin or the chapter book, Esperanza Rising by Pam

Munoz Ryan.

The deeper and richer the literature, and the stronger the characters, the easier it will be to include character education naturally in literature study. If a book is well-chosen, the characters will probably display many different traits worth emulating, and will apply these in situations young readers can understand and identify with. All it takes is a bit of practice in focusing our attentions in this area. So now let us examine some excellent children's books with the intention of using them to integrate character education.

Books to Live By

Picture Books

Miss Rumphius by Barbara Cooney follows the life of an atypical woman who travels widely, never marries, and follows her independent idea to improve the world. We meet Miss Rumphius as a young girl when her grandfather tells her she must do something to make the world more beautiful. We leave her as she is passing this challenge on to her young niece. Throughout her lifetime Miss Rumphius exhibits independence, resilience, courage and care for the environment.

Strategy for use. This story lends itself easily to students writing either a journal entry or a book of their own. First, discuss the importance of goal-setting, and consider what a person should try to give back to the world. Miss Rumphius’ three goals were to go to far-away places, come home to live by the sea, and do something to make the world more beautiful. Ask students what their three goals would be, then lead them to write stories about their own future lives entitled, Miss__________ or Mr. ___________.

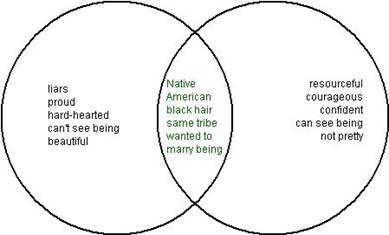

The Rough-Face Girl by Rafe Martin is a Native American Cinderella variant in which two proud, but beautiful, sisters do not marry the desirable Invisible Being because of weaknesses in their characters. The Rough-Face Girl is not beautiful, but she has a pure heart and is judged worthy to marry the Invisible Being because she alone can see him.

Strategy for use. Cinderella stories make a very clear distinction between good and bad people in the story. There is no ambiguity, and this often makes it easier for young children to discriminate between noble and ignoble character traits. An easy graphic for doing this sort of comparison is the Venn diagram. A Venn diagram comparing the traits of the evil sisters and the Rough-Face Girl might look like this:

SISTERS ROUGH-FACE

This graphic should then be followed with ample discussion focusing on why children chose to include the traits they did, what evidence from the story do they have that these traits existed, and what distinguishes good from bad in the characters.

A Chair for my Mother by Vera B. Williams, is about a matriarchal family consisting of a grandmother, a single mother and a little girl who work together to rebuild their lives after their apartment burns. Their neighbors and extended family help them with many necessities, but it is up to the three of them to save the money to buy a soft chair. The story highlights the virtues of resilience, cooperation, courage and love, though none of those words are ever mentioned.

Strategy for use. Ask students to find a favorite quote in the book and write this on an index card. The quotes should tell something about the virtues or values of the character. Put these index cards in a stack and draw one or two of them each day to begin your discussion of the book. The student who wrote the quote could be asked what he/she saw as the character traits exhibited in this quote and could lead the discussion of that day. Examples of quotes from this book include:

Girl: And every time, I put half of my money into the jar.

Girl: We went to stay with my mother’s sister Aunt Ida and Uncle Sandy.

Grandma: It’s lucky we’re young and can start all over.

Chapter Books

The Hundred Dresses by Eleanor Estes, is an easy chapter book suitable for transitioning between picture books and longer works. In The Hundred Dresses a clique of popular girls makes fun of an outsider by teasing her about her funny name and the poverty she lives in. One of the girls in the group, Maddie, does not like what is happening but makes no effort to stop the teasing. The girl, Wanda, also makes no effort to defend herself. When she moves away suddenly and it is discovered she really did have 100 dresses (beautiful drawings she had made) the clique of girls, especially Maddie has no way to assuage their guilt over their teasing.

Strategy for use. In the way the story currently ends, Maddie learns many valuable lessons but is never able to apply them to Wanda. This book is a perfect choice for doing a “choose your own adventure” rewrite with children. Stop after Wanda does not defend herself, and ask students to write a new ending in which she does. Or stop after Maddie feels guilty but takes no action, and write a new path for her in which she stops the teasing. Or help Maddie find Wanda after she moves away, and write a path that allows Maddie to make peace with Wanda. This story has lots of alternative ways it could go, and the discussion surrounding the different choices will be rich in character education.

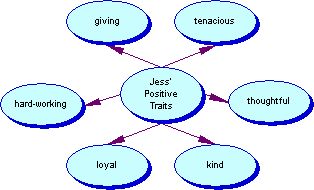

Bridge to Terabithia by Katherine Paterson is a book about two fifth-graders who find in each other a kindred spirit. Both have complex and integrated personalities, and this sets them apart in their fifth-grade classroom which is rampant with gender stereotyping. In addition to this non-stereotypical integration both Jess and Leslie display many other admirable qualities. Jess is a scapegoat at home, yet he deals kindly for the most part with his sisters and parents. He has the great gift of self-reflection and when faced with a moral dilemma he recognizes it and tries to think through the right thing to do. For example, when he is faced with a bully who is picking on his little sister, Jess understands the need to stop the bullying but also recognizes that the bully is a person who deserves compassion. Leslie’s circumstances also require her to be noble. She especially lavishes this nobility on Jess, showing him compassion, kindness, loyalty and humility. While she often serves as the leader of the pair, she also humbly recognizes the many gifts Jess brings to the friendship.

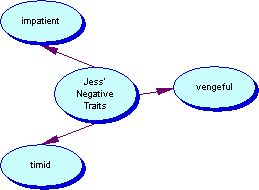

Admirable as Jess and Leslie are, however, they are not perfect. Leslie is deceitful with her teacher, and

vengeful with the class bully. Jess is

sometimes impatient with his little sister, and one time even hits her. Far from making these characters less

admirable, the existence of negative character traits and their struggles with

these are what make Jess and Leslie such good role models.

Strategy for use. Have students make clusters or webs using the positive and negative traits they find for the two main characters. On one large sheet of paper put Positive Traits in the center circle. On the other, write Negative Traits in the center. Students should print traits on the appropriate web and then put the page number where this trait was displayed. Use these clusters as the beginning of discussions about noble behavior, or lack of, and then apply these traits to students’ own dilemmas. Here is an example of possible clusters for Jess:

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle is another classic book peopled with imperfect but noble characters. As in Bridge to Terabithia the main characters in Wrinkle also display many admirable traits, such as courage, compassion, discipline and honesty. Meg and Charles Wallace, who are brother and sister, and their friend Calvin, all set out on a fantasy journey to rescue Meg and Charles Wallace's father from the evil It. In this good versus evil story, Meg especially is called upon to mature quickly. The journey requires her to become more self-accepting, more confident, more courageous and more giving than she had previously been in her school-day life.

Strategy for use. This book has a rather difficult writing style, and students may need help in discerning the deeper meaning behind some of the happenings. A good way to address this need in the classroom is to ask students to keep a double entry journal in which they write actual quotes from the book on the left side and their interpretations of these quotes on the right. Using these journals as discussion starters will bring out the virtuous character traits that are woven everywhere throughout this book, but are sometimes partially obscured for children by the difficult language. Here is an example of a double entry journal for this book:

WHAT HAPPENED WHAT I THOUGHT

Mrs. Whatsit gave Meg a gift of her faults. p.100 How can faults be a gift???

Charles Wallace was making jokes and Meg said Does that mean he is trying not show

it was his way of whistling in the dark. p. 117 that he is afraid?

The evil It says, “I am peace and utter rest. He sounds really nice, but Meg

I am freedom from all responsibility.” p. 130 shouldn’t trust him!

More

Books to Live By

These are only six books of a multitude of high-quality children's books that can be used for integrating character education into an already full school program. As the sample activities for these books show, infusing character education into literature study is more a matter of a slight change of emphasis rather than a new topic. Instead of examining characters as a literal concept in relation to plot and setting, examining character traits critically in relation to the virtues takes only a small shift in the teacher's intent. Here are several more books that could be used easily for character education:

Picture Books Chapter Books

Emily by M. Bedard Chevrolet Saturdays by C. D. Boyd

Fox Song by J. Bruchac Bud, Not Buddy by C. P. Curtis

Flower Garden by E. Bunting Letters from Rifka by K. Hesse

Seven Silly Eaters by M. Hoberman No Pretty Pictures by A. Lobel

Toads and Diamonds by C. Huck The Moorchild by E. McGraw

Mufaro’s Beautiful Daughters, J. Steptoe Same Stuff as Stars by K. Paterson

Thundercake by P. Polacco Esperanza Rising by P. M. Ryan

Gittel’s Hands by E. Silverman Holes by L. Sachar

William’s Doll by C.Zolotow Tuck Everlasting by Natalie Babbitt

A Picture Book of Eleanor Roosevelt Ella Enchanted by G. Levine

by R. Casilla

Conclusion

Including

character education is appropriate for teachers in public schools. Historically, and by societal demand,

character education is an expected part the public school's work. And inevitably, character education will happen during the elementary

years. The only question is what sort of

character will be developed in children during these years. Intentionally including discussions on

character in literature study can help assure that children develop characters

that know, love and do good. As

teachers, this is perhaps our most important work.

Bibliography

Bettelheim, B.

(1989). The uses of enchantment: The meaning and importance of fairy tales.

Guroian, V.

(1998). Tending the heart of virtue: How classic stories awaken a child's moral

imagination.

Josephson Institute on Ethics. (2000). Available at www.charactercounts.org.

Kilpatrick, W.,

Wolfe G., & Wolfe, S.M. (1994). Books that build character: A guide to teaching

your child moral values through stories.

Leming, J. (2000). Tell me a story: An evaluation of a literature-based character education programme. Journal of Moral Education, 29 (4), 413-426.

Lewis, C.S. (1947). The

abolition of man.

Lickona, T.

(1991). Educating for character: How our

schools can teach respect and responsibility.

Noddings, N.

(2002). Educating moral people: A caring alternative to character education.

O'Sullivan, S.

(2002). Character education through children's literature.

Ryan, K. (1996). Character education in the

Ryan, K. & Bohlin, K.E.

(1999). Building character in schools.

Vessels, G. & Boyd, S.M. (1996). Public and constitutional support for character education. NASSP Bulletin, 80 (579), 55-62.

Wynne, E.

(1992). Transmitting character in

schools: Some common questions and answers.

Clearing House, 68 (3),

151-153.

Children's Books

Cooney, B. (1982). Miss Rumphius.

Estes, E. (1944). The

Hundred Dresses.

L'Engle, M. (1962). A

wrinkle in time.

Huck, C. (1989). Princess furball.

Martin, R. (1992). The rough-face girl.

McGraw, E. (1996). The moorchild.

Paterson, K. (1977). Bridge to Terabithia.

Paterson, K. (1991). Lyddie.

Polacco, P. (1990). Thundercake.

Ryan, P. M. (2000). Esperanza

rising.

Williams, V. (1982). A

chair for my mother.